Stolen Rainbow: The Great Unmasking

Martin Mawyer is the author of Stolen Rainbow: The Great Unmasking, which maps how the LGBTQ movement rose to political dominance after stealing the symbol of God’s covenant rainbow.

Until the 1970s, the homosexual movement wasn’t a movement at all. There were no gay rights parades, much less an alphabet-soup of LGBTIQA+ services and celebrations.

No one had heard of GLADD, the National LGBTQ Task Force, the Human Rights Campaign, or Lambda. They didn’t exist.

Before the ‘70s, gays were mainly in the closet, unorganized, powerless, and without two nickels to rub together and spend on political action.

There were no openly gay lawmakers, actors, business executives, teachers, or presidential candidates.

The gay rights movement before the ‘70s? Draft dodgers of the Vietnam War had more political power.

So how did gays and lesbians go from being the hapless political dwarfs they were 50 years ago to being the powerhouse fat cats they are today?

The answer can be likened to a three-stage rocket, with each successive propellant boosting them nearer to political dominance. The last stage will surprise you.

Stage One: Stonewall Riot

The Primary Stage was the 1969 Stonewall Riot.

Much has been written, said, and opined about this riot, usually with a huge dollop of biased and revisionist LGBTQ platitudes.

On June 28, 1969 the New York Police Department raided the Stonewall Inn, a bar in Greenwich Village. Officers were looking for underage drinkers and illegal booze being sold to a predominantly homosexual, cross-dressing clientele.

The mafia owned the Stonewall Inn, and the raid was not unusual in that the establishment did not have a license to sell alcohol.

During all previous raids, the booze and the cash would be seized. A few patrons would be ticketed if they violated New York City’s dress code requiring people to wear at least three pieces of clothing specific to that person’s gender.

Deputy Inspector Seymour Pine, the officer in charge that night, said there was no intention to arrest anyone.

The largely transvestite patrons were on edge, however, having had enough of being kicked out of their lone social and drinking club in the Village and being ticketed for wearing the wrong attire.

One protester said, “Our goal was to hurt those police. I wanted to kill those cops for the anger I had in me.”

After the LGBTQ boozers exited the inn, they suddenly barricaded ten police officers inside and began rioting on Christopher Street. Someone lit a fire. Firebombs were thrown into the bar.

Inspector Pine would later say, “It was terrifying. It was bad as any situation that I had met during my entire time in the Army.”

The riot lasted through the night.

The following day, after the smoke and tired protesters had cleared, the gay rights movement had been conceived.

Twelve months later it would give birth to the first-ever gay pride parades, with events held in New York City, Los Angeles, Chicago, and San Francisco.

Attendance, however, was meager compared to the size of today’s pride events.

“A tiny band of hippies and ‘hair-fairies,’” is how the GLBT Historical Society Museum described the size of the San Francisco pride march.

Small bands of gay demonstrators piggybacking off a violent riot that injured policemen was hardly a winning strategy back in the 1970s. The American pubic was unsympathetic.

But the Stonewall Riots did create solidarity for homosexuals, much like Rosa Parks – the black woman who refused to give up her seat to a white person on a public bus – became a defining moment for the civil rights movement.

(The fact that one was peaceful and the other so violent speaks volumes about the ideological difference between these two minority movements.)

With unimpressive attendance at their Pride rallies, the LGBTQ movement of the 70s needed some additional propulsion.

Stage Two: Rainbow Flag

The rocket’s Second Stage lifted the LGBTQ movement into the stratosphere. It came in the form of a flag – a rainbow flag.

LGBTQ activists needed a banner they could rally under, a flag with a message of unity that could attract straight sympathizers, a social masthead that could inspire nervous gays and lesbians to come out of their closets and join the cause.

What better symbol could there be than one that spoke of love, harmony, acceptance, unity, and peace – namely, God’s very own rainbow?

So, they stole it.

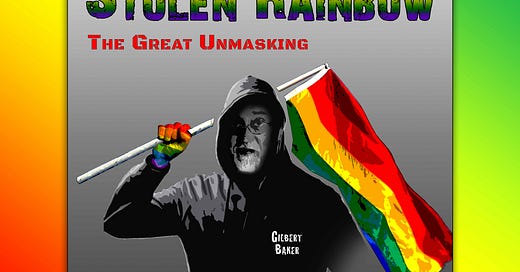

In 1978, organizers of the San Francisco Gay Freedom Day Parade selected Gilbert Baker, a known gay rights activist and artist, to design the flag.

Baker was a member of the Sisters for Perpetual Indulgence, a drag queen group known for its flamboyant makeup and mockery of Christians.

From its inception, the rainbow flag was as much about assailing Christians as it was about gathering gays and lesbians under an umbrella of unity.

In a recorded interview, Baker would say, “I’m all about working every last nerve of the Church.” He would later call a photograph taken by artist Andres Serrano of Christ submerged in a jar of the artist’s urine “a very beautiful photograph.”

To anger Christians even further, Baker would later dress as a “Pink Jesus” and stage a public mock crucifixion of himself on a cross, claiming Jesus was executed because he was a homosexual.

Still, regardless of Baker’s tasteless bullying of Christians, the rainbow flag gambit paid off.

When the 28-foot rainbow flag was unveiled in San Francisco on June 25, 1978, there were 250,000 spectators in attendance.

Subsequent gay Pride rallies saw their numbers increase throughout every major city in the United States. For example, in 1979, between 75,000 and 125,000 gay-rights attendees showed up at a Pride event in Washington, D.C.

Stage Three: AIDS

Not long after, the final booster of that rocket was fired. When it first ignited, it didn’t look like something that would propel the LGBTQ movement to “infinity and beyond.” Actually, it looked more like a nuclear missile and the LGBTQ movement like Ground Zero.

In the end, however, that last boost of acceleration would rocket LGBTQ to “where no man has gone before”: to being arguably America’s most potent political movement.

I’m talking about AIDS.

When AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome) was first diagnosed in 1981, it had all the hallmarks of a disease that would destroy the gay rights movement. For a while, it did.

AIDS was a disease almost entirely transmitted from homosexuals to homosexuals. But back in 1981, a worried public feared they were equally vulnerable to catching the deadly sickness with a life expectancy of just two years.

To the surprise of no one, gays and lesbians suffered the wrath of an angry public that held them directly responsible for the disease.

Homosexuals went back into the closet. Gay bars and bathhouses were shut down. There were reports of funeral homes that wouldn’t accept the bodies of AIDS victims. Even some hospitals turned away AIDS patients.

Of course, it didn’t help that Life magazine put this alarming headline on its July 1985 cover: “No one is safe from AIDS.”

Donna Shalala, secretary of Health and Human Services under President Bill Clinton, told Congress that the spread of AIDS could lead to “nobody left.”

Nobody left? No one is safe?

Panic naturally set in, and no one was talking about Gay Pride any longer.

But AIDS, a disease that should have set the gay rights movement back fifty years, actually became its breakthrough moment.

Billions of dollars were poured into the gay rights movement to help cure the disease and provide medical relief to those suffering from its debilitating effects. The money came through taxpayer funds, philanthropical donations, private gifts, and world relief contributions.

By 2015, the total global spending on HIV research, treatment, and prevention topped half a trillion dollars.

Anyone who thinks that money was used solely for medical research, hospital bills, medication, and housing for those with AIDS or HIV is in denial.

For instance, in March of this year, one of New York’s most prominent LGBTQ organizations lost $10 million in annual state funding after The LGBT Network of Long Island was caught mishandling taxpayer money.

“The group,” the N.Y. Post writes, “billed itself as the premier LGBTQ provider on Long Island that fulfilled a range of crucial services to the vulnerable community, including housing, substance abuse help and HIV prevention services.”

Except, where did those millions of tax dollars go? To save the sick? Or to promote the LGBTQ agenda?

The State of New York doesn’t know, and the LGBTQ group isn’t saying.

No one disputes, however, that the LGBT Network is one of the nation’s most powerful political gay-activist groups.

Government money – those billions of dollars given to the LGBT cause – has vanished into a deep dark hole, and no one cared if funds meant to provide medical care and relief to AIDS/HIV patients have been spent promoting drag queen shows, transgender pronouns, gay rights legislation or a host of other Gay-Pride-activist goodies: gay adoption, trans men competing in female sports, gender-neutral bathrooms, etc.

With their own “Rosa Parks” moment at the 1969 Stonewall Riot, and their rainbow-flag rally banner flying high in 1978, all that was needed was cash for activism and lots of it.

AIDS would become that financial aid they were looking for, giving them millions of taxpayer dollars to achieve their ultimate goal: To work “every last nerve of the Church.”

Get the book:

it is evil infiltration that did this and these abominations are not gay not happy at all to do such queer acts

Excellent article. I learned a lot about the homosexual quest for political power.